Doc, What’s My Bill?

Art is therapeutic, right? It gives your eyes something to look at, your rational brain something to think about, AND that overgrown reptilian brain way down inside a focus for reaction.

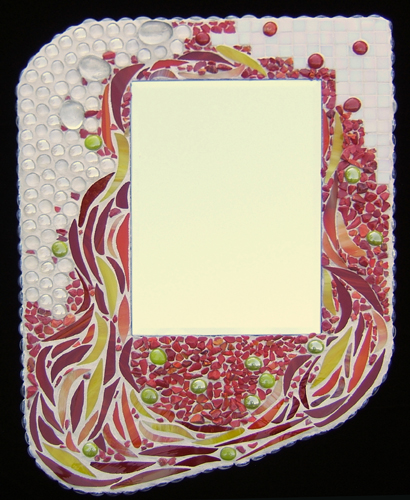

Autumn Fires Mirror

by Lynn Bridge

So now that you find yourself in the doctor’s office (your local art gallery), and you are looking at those prices, what is going through your head? If you are new to buying art, quite likely there is some amount of sticker shock!

What, exactly, are you paying for when you buy a piece of art?

Of course, you already know that you are paying for the materials. Generally, a higher ratio of pigment to binder in paint means a more expensive brand. Also, certain pigments are far more expensive (and toxic for the artist) than others, so those classes of paints are more expensive than their cousins.

Casting a bronze sculpture requires a small army of people, in addition to the artist, to carry out. They all need to be paid, as does the supplier of metal and equipment.

Printmaking can require a lot of equipment, too, which is part of the overhead cost of running an art studio. Fortunately, with both casting and printmaking, a number of copies (not all identical) can be made from the mold or the plate.

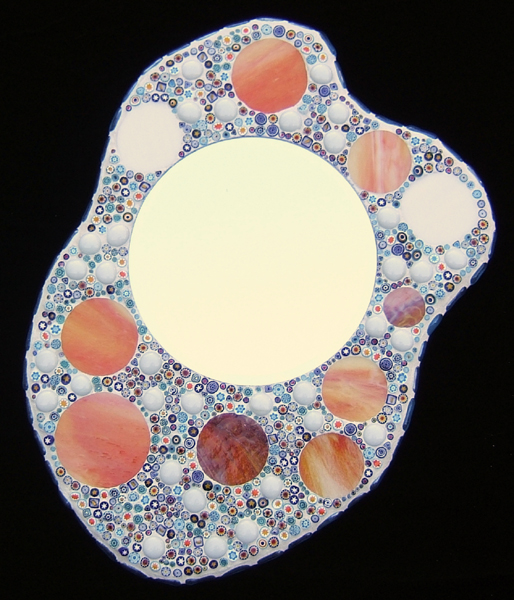

Mosaic materials can range from inexpensive (cast-off broken china and creek rocks) to costly (gold-leaf embedded in glass).

Planetary Field Mirror

by Lynn Bridge

You also know that you are paying the artist for her time and her talent, and just as in other professions, this varies by experience and by the technique she is using.

There is also a big unknown quantity, and that is the artist’s popularity. The price of the artist’s time rises with the ‘collectibility factor’ of his work. You might be surprised to know that many hobbyists charge much less than minimum wage for their time, and even professional artists with years of experience rarely make a living wage from selling artwork alone!

In a good year, an artist might only sell 40% of the pieces he has made, so the time he has put into making the other 60% does not pay off immediately, and he makes no wages for that work he has put in.

Part of what goes into the price you see on the label next to the piece in the art gallery is the cost of running an art studio, most of which is ongoing regardless of whether or not pieces are being made and sold from it. Power, water, furniture, rent, specialized equipment, replacement, insurance, countless trips to-and-from the shipping center, the art store, Home Depot, and the many art galleries add up quickly, just as they do in any small business. Your artist spends a certain amount of money on books and periodicals to stay current with the art world in general, and techniques and methods in particular. Same for continuing education classes. Framing is costly, too, and some galleries offer flat art at both framed and unframed prices.

Did you know that most galleries charge the artist a commission of 100% to sell their work? Some still only charge 80%, but some are now over 110%. So, take a look at that price on that painting and realize that your artist is receiving half that amount for her work and for her expenses! Paying the gallery to market and sell work is invaluable for busy artists who make lots of sales. They are able to concentrate more of their time on making the art, rather than marketing and selling. ( There is no artist who can rely entirely on a gallery for publicity and sales. )

Artists must maintain a public face and must constantly spend time away from the easel in order to publish blogs, make brochures, announcements, and newsletters for their collectors and potential collectors; inventory work; keep scrupulous business records; visit galleries and see other artists’ work; attend art show openings; and keep up the facebook profile and a stream of twitter announcements.

You might say, “Well, why don’t I just buy from the artist directly and save myself the markup of an art gallery?” That is a good question, but there are reasons why this is not an acceptable practice. For one thing, as an artist’s career is getting good traction and you have actually HEARD of the artist and are considering buying his work, one big reason this is happening is that the gallery has bothered to advertise, get publicity through news outlets, and generally maintain a high enough profile for you to notice. You might guess that this all takes time and money- costs which have already been spent and which are going to be reflected in the price of the art, even if you buy directly from the artist.

Another reason why buying at a lower price directly from the artist is false economy is that NO ARTIST SHOULD UNDERCUT HER GALLERY. The gallery has already done the work (see previous paragraph). If this is not the case and the artist does not even show in galleries, SHE STILL NEEDS TO CHARGE YOU FOR ALL THE TIME AND MONEY SHE HAS SPENT TO FIND YOU! In other words, if the cost of marketing does not go to a gallery, it does go to the person who has put in the time and money.

Think about retail. What store does not reflect its advertising costs, marketing costs, storefront costs, etc. in the price you pay for its merchandise?

When you look at your ‘medical bill’ for art from this perspective, it starts looking like a better and better deal all the time! Not only can you enjoy the work during your lifetime, but, if it is the sort of art that is durable, your children and grandchildren can enjoy the work, too. What an investment in the life of a family or a community!

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Self-aggrandizing announcement: One of my pastel paintings, Incursions 3, won a first prize in the painting category at the Georgetown Art Hop 2010. I have two pastels juried into the show. Details are on the Where to See My Art page.

I wish I had a scanner to post a copy of a cartoon I drew this week that was on this same issue, only with regard to music lessons!

LikeLike

Don’t need a scanner- can you borrow a tripod to use with your camera? I’d like to see your cartoon.

LikeLike

Actually I have a tripod, and I already tried this. It’s just that the cartoon is pencil, so maybe I need to try it in different lighting for it to really show up on camera.

LikeLike

Hey Lynn – this is a great article on artists costings and why people dont get paying a reasonable price for art work.

CONGRATULATIONS!! on your win – Well done – looks like a great piece.

LikeLike

Kadira- thanks- and pass this on to others who question the cost of art, if you think my post would be helpful. Anyone who has not owned a business usually underestimates the cost of doing business.

LikeLike

Great post Lynn!

LikeLike

Thanks, Greta. Just spreadin’ the news!

LikeLike

GREAT POST!!

Thanks for sticking up for all artists with this clear and informative article. If I tackle this subject, I will link to this post for sure!

LikeLike

Hi, Hannah. I think that if artists busy themselves with educating the public in general about these things, people might see what we do in a new light.

LikeLike